In his May press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell cited what he believed were “transitory factors” that resulted in a low inflation print over the past 12 months, reports money manager Monty Guild in an exceptional in-depth overview of technology and deflation in his Guild Investment Global Market Commentary.

Although many economists and officials talk about inflation data as if they were precise and uncomplicated, many others believe that official data are significantly overstated.

The calculation of accurate inflation numbers affects almost everything in finance and economics — but the reality is that current mainstream calculation methods don’t take enough account of the enormous deflationary forces being wrought by digital technologies.

These technologies are bringing on “supply side shocks” in many areas of the global economy by permitting a more intense and efficient utilization of resources, as well as by the substitution they are able to make in which software disrupts and replaces many established goods and services.

The statisticians (as usual) have yet to catch up. This downward pressure on inflation is likely to be persistent, not just transitory -- giving the world’s central banks more flexibility with “easy money” policies without threatening to summon the specter of inflation.

Many economists and officials are perplexed by what they see as persistently and worryingly low inflation. Such worries have never been far from the surface in the period after the financial crisis and the Great Recession.

The assessment of inflation is a critical process for countless private and government analysts, and the consequences of arriving at a given number are profound. Cost-of-living adjustments, Federal Reserve interest-rate policy decisions, and assessment of stocks’ valuations can all hinge in part on what inflation number goes into the analysis.

Pretty much every economist trying to figure out the big picture of the economy’s performance is relying on accurate inflation statistics in one way or another. However, it’s likely that the methods of calculating the official numbers are outdated.

This is not a controversial statement. While some analysts and many government officials still discuss inflation statistics as though they weren’t problematic, others are more willing to admit that the whole approach to inflation needs a deep rethink… and that the numbers are not reliable.

They’re not just off by a few tenths of a percent. They’re likely off by several percentage points — if it even really makes sense to talk about a single inflation number covering the whole economy. And that single number is likely too high.

“Transitory Factors”

In Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s press conference two weeks ago, he noted that “core inflation” (which strips out the prices of volatile items such as food and energy) had “unexpectedly” dipped in the previous 12 months.

He said, “We suspect that some transitory factors may be at work.” Stock markets proceeded to work themselves up over the word “transitory,” engaging in the kind of arcane prognostications of Fed speak that have become typical for the post-crisis period.

We don’t believe the forces depressing inflation are transitory. Rather, we think they are profound and likely to last longer and intensify.

The Digital Revolution

The primary culprit is technology. We’ve often discussed the different stages of industrialization through which societies pass. The first industrial revolution consisted of steam power, railroads, steel, and the first mass production.

The second consisted of electricity, the assembly line, and chemicals. And the third arises from computers and digital communications.

Many economists have noted that all technological revolutions are basically deflationary -- they create “supply side shocks.” That is, they allow for more intensive use of resources, and thus higher production -- and with more goods being produced, all other things being equal (as economists like to say), the price of those goods will fall.

The digital revolution — enabled by computer technology and electronic communication — is doing the same thing. However, the deflationary impulse is pervasively spread across economic sectors where its presence has been difficult to note.

For example, how can there be a “supply-side shock” with land and property? Surely the supply of land is largely fixed, particularly in areas that have already been urbanized. Some additional capacity was created by technologies of the second industrial revolution, such as increasingly taller high-rise buildings.

But a company like AirBnB showcases how digital technologies are allowing more intensive resource utilization. There was a lot of accommodation capacity hidden in the world’s cities — but it was not accessible until the internet, smartphone adoption, and AirBnB’s founders’ ingenuity unlocked it.

As a consequence, available accommodations in U.S. cities have risen by 25%. The established hospitality industry has had its well-being disrupted as a consequence, and companies are belatedly joining the party.

Ride-hailing companies Lyft (LYFT) and Uber (UBER) have come to public stock markets, with analysts now scrutinizing their balance sheets and questioning their forward paths to profitability.

We are skeptics about their business model. We also see gathering clouds of regulatory action and labor strife, and we believe they may be depending on over-optimistic assessments of the timeline for self-driving technology.

Whether or not these companies become profitable, and however their stocks ultimately perform in public markets, they are responding to a genuine economic reality: the stock of motor vehicles is woefully under-utilized.

The average passenger car in the U.S., for example, is in use about one hour a day; it has a capacity of five passengers, and on average carries only 1.55. Together, those imply a capacity utilization for the U.S. passenger vehicle fleet of about 1.3%.

Ride-hailing services are addressing that severe underutilization, effectively bringing more “available passenger miles” to market at relatively minimal cost (compared to constructing a new vehicle and additional transport infrastructure). All other things being equal, this will drive down the cost of a passenger mile — that is, it’s deflationary.

That doesn’t even account for the second-order effects -- for example, the productivity consequences of more time spent working rather than driving, or the deflationary feedback of parking capacity being repurposed for commercial and residential real estate.

E-commerce itself has similar effects. As consumers concentrate their attention on e-commerce platforms, comparison shopping becomes easier and more efficient. How often have you found yourself buying a cheaper version of an item showcased in Amazon’s (AMZN) “customers who viewed this item also viewed” box?

Academic studies that distinguish online from physical retail shows a suppression of inflation in the online venue. How big is this effect, and how pervasive? We don’t know, but it is certainly real.

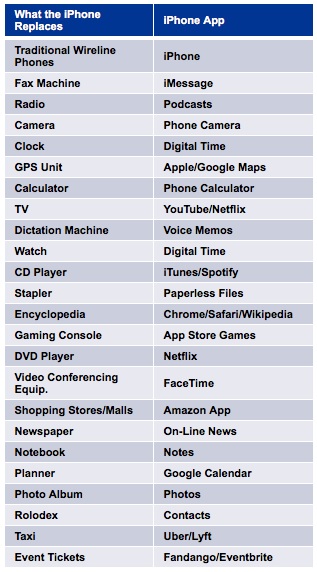

That’s only three of the most obvious areas. But when you consider all the items replaced by the software on a smartphone, you can see that thinking through all the deflationary consequences of the digital revolution is not a trivial task.

Source: BlackRock

Other Factors At Work

Many analysts have pointed out that there are other forces at work as well, which are not technological although they may be tangentially related. One of the major ones is demographics; as consumers age, they consume different goods, and generally, less of them (particularly consumer goods, though obviously not health care).

The aging of populations and the slowing of population growth is apparent worldwide, even in most developing countries. Immigrants from developing countries quickly converge to the low population growth trends of the developed countries to which they migrate. These are trends that, contrary to Mr Powell’s suggestion, are unlikely to be transitory.

Some current deflationary trends are indeed likely to shift: for example, the greater savings rate of American consumers that has happened as a result of the trauma of the financial crisis, or the U.S. specific price declines that have followed from the dollar strength of the last few years that has made imports cheaper for Americans. But these, we believe, are not driving the bulk of the deflationary effects.

How Economists and Governments Miss the Deflation

Because of the way official statistics are compiled, the deflationary effects noted above are not generally captured in old school inflation numbers — numbers generated with analytical models built before the arrival of the digital revolution.

The problem hinges on substitution: by the time the analysts begin tracking the price of a given technological item, it has already displaced a host of older consumer goods. The decline in a smartphone’s price is statistical peanuts compared to the effects it already had on a vast swath of goods and services while statisticians weren’t yet watching it.

This effect is pervasive, even if we don’t yet have an analytical handle on how big it is. So when you see references to inflation in the news, or in securities analysis, recognize that the models and axioms of the past may be less helpful.

Investment implications

Assessing the macroeconomic environment accurately is the first part of a sound investment process (followed by bottom-up analysis of the securities one is evaluating).

Realizing that official inflation statistics are likely overstated will lead to a different assessment of that environment, and particularly, of the likely path of monetary policy. We believe that inflation is muted and deflationary trends are present not for transitory reasons, but for lasting structural reasons.

Subscribe to Guild Investment Global Market Commentary here…