Changes in trend are always the most difficult periods to navigate in financial markets, economics, and geopolitics, states Simon Ree of TaoOfTrading.com.

And when changes are happening in trends that have been in place for 40 years? Well, very few believe such a change in trend is even a possibility. This note is on why I believe this is a possibility we all must consider today. Globalization and its impact on inflation.

Let’s begin by looking at a major reason why inflation has not been a problem in the last 30+ years: Globalization.

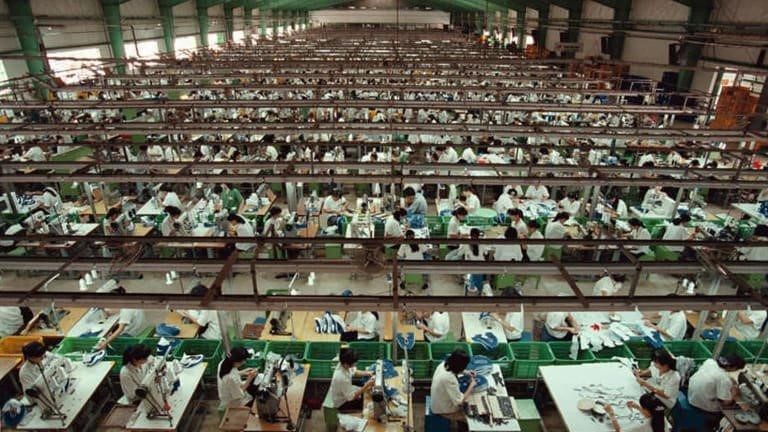

The process of globalization began in earnest in the 1980s under Reagan and Thatcher. It then continued with the collapse of the Soviet Union/fall of the Berlin Wall and the creation of the European single market. Globalization really accelerated after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Chief among the benefits of globalization for “the West” was the ability to cut costs (aka “maximize shareholder value”) by offshoring manufacturing and supply chains to geographies with relatively cheap labor costs.

Western economies received a rude awakening to the risks of supply chain disruptions and component dependency/deficiency during the Covid pandemic. The global semiconductor shortage is a stark example of this. Much of this disruption is an unintended consequence of the enthusiastic push towards globalization that began in the 1980s.

It is by now obvious to everyone that:

- Inflation has continued to accelerate in the the West; and

- It is not “transitory”

The economic and social implications of this are significant. Inflation will affect nearly everyone. And it will affect the majority of people negatively (I have much more to say on this in a future note).

Interdependence—the End of an Era

The risks posed by the trifecta of military, food, and energy/commodity interdependence have rapidly dawned on the West following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Still reeling from Covid-related supply chain disruptions, the sanctions imposed on Russia have added further pain. Energy prices, industrial minerals, fertilizer, and agricultural commodity prices are all soaring, their combined impact is likely to support inflationary conditions for months to come.

Even if Covid and the Russia/Ukraine war were to end tomorrow, the West (and many emerging economies) will be focused on reshoring manufacturing and supply chains to ensure a much greater degree of food and energy sovereignty and security. Investments in military are also likely to increase. Investments in areas today considered taboo by many—e.g. shale and nuclear—are also likely to increase.

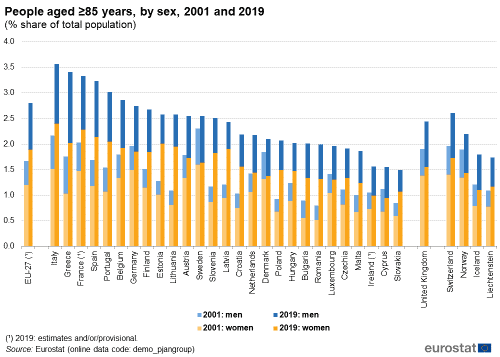

As a result, demand for skilled labor is likely to rise quickly in the West, at a time when demographics (particularly in Europe) and labor force participation rate trends are not supportive.

A Long-Term Fundamental Shift is Underway

The economic impact of all of this? Higher production costs. This is going to run counter to the previous trend of downward pressure on production costs brought by globalization. Increased demand for skilled labor will result in higher wage inflation. This, combined with higher capital investments (e.g. the onshoring of semiconductor manufacturing), will result in lower margins and/or higher prices.

Since the 1980s, globalization (offshoring of manufacturing and supply chains) has manifested in the West as downward pressure on inflation, downward pressure on interest rates, and steady improvement in corporate profit margins. There is a serious risk that these trends are all now being reversed. This is almost unthinkable for many, because these secular trends (disinflation, declining interest rates, improving margins) are all that most of the current working-age population have known.

But Interest Rates CAN’T Rise!

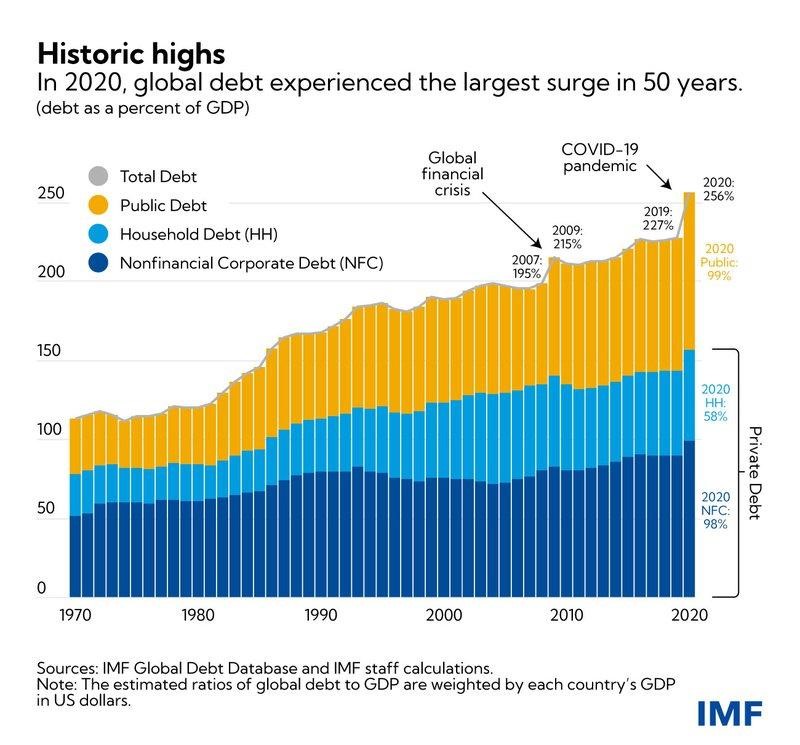

This is a common belief, largely held by people too young to have ever seen a secular rising interest rate cycle. The premise is extremely simplistic: Interest rates CAN’T rise much because if they do, “something will break.” Well, maybe something is going to break. My friends, things have ended up breaking in the past, so let’s at least entertain the idea. Sovereigns, businesses and households today are all highly leveraged. A highly levered environment requires constant growth and low borrowing costs to avoid the possibility of “something breaking.”

A commodity shock by itself makes growth more difficult. Trade wars, economic wars, supply shortages...all are impediments to growth. The strongest Inflationary trends we’ve seen in 40 years will make keeping borrowing costs (interest rates) low difficult. In a highly leveraged system, debt repayment becomes a significantly larger burden when growth slows down and interest rates rise. Think rising defaults, lower growth, currency devaluations, stagflation, recession, credit crunch. These things are all possibilities...the one certainty going forward is increased economic volatility.

Can the Fed Save the Day?

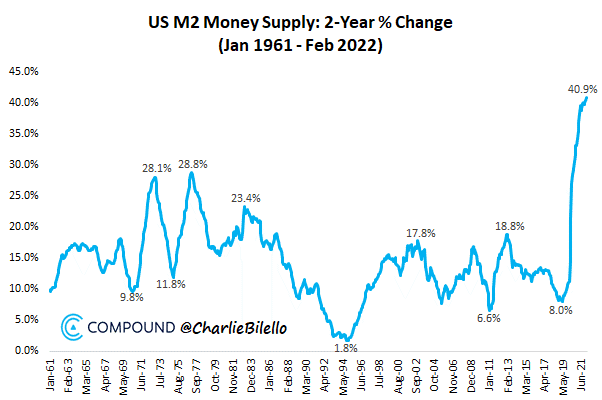

By being so far behind the curve, the Fed has contributed much towards the inflation problem we are now experiencing. Maintaining policy at emergency levels of accommodation, in an economy that was already recovering well AND was the recipient of an additional $1.9 trillion in fiscal stimulus was a major policy error.

Expectations for terminal interest rates are now being ramped up, as a direct result of the Fed being so far behind the curve. Citi are now calling for 50bp hikes at each of the next four FOMC meetings, reaching a policy rate of 2.75-3.00% by the end of the year. Where terminal rates end up is anybody’s guess...but a terminal rate of 5.0% has been pretty normal since the 1990s (and much higher than that prior to the 90s).

As a result of being so far behind the curve—with the Ukraine war adding further consequence—the Fed likely has just two choices here:

1) Fix inflation by causing a recession (this is basically what Powell has been saying recently); or

2) Let inflation continue to rip for many more years.

They have run out of good choices. A softly, softly approach will be ineffective; a fact that everyone seems to be slowly waking up to.

Bond markets do NOT like these two alternatives...

...which is why we are seeing greater volatility in bonds today than we are in equities. As of Friday’s close (25th March 2022) implied volatility on iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) was 24.1%, compared with S&P 500 ETF (SPY) at 22%. This is a highly unusual—and unhealthy—market condition.

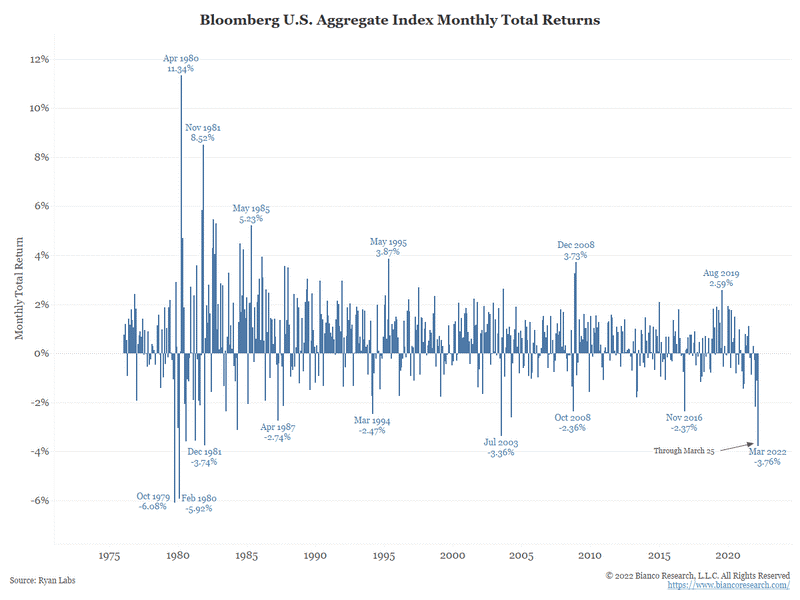

As this chart shows, bonds are off to their worst start of the year since 1982:

Source: Bianco Research

The traditional role of bonds in a diversified portfolio is to:

- Provide a source of regular, reliable income

- Preserve capital

- Hedge against a slowdown in economic activity—which is usually bad for stock prices but good for bond prices

One could argue that—with deeply negative real interest rates—bonds are failing at all three of their traditional roles today.

It makes for a particularly challenging investment environment when bonds and stocks are falling simultaneously, because there is nowhere to hide. And if bonds are at a major turning point in terms of their long-term trend, this will only add to financial volatility and uncertainty going forward. Especially compared to the last decade.

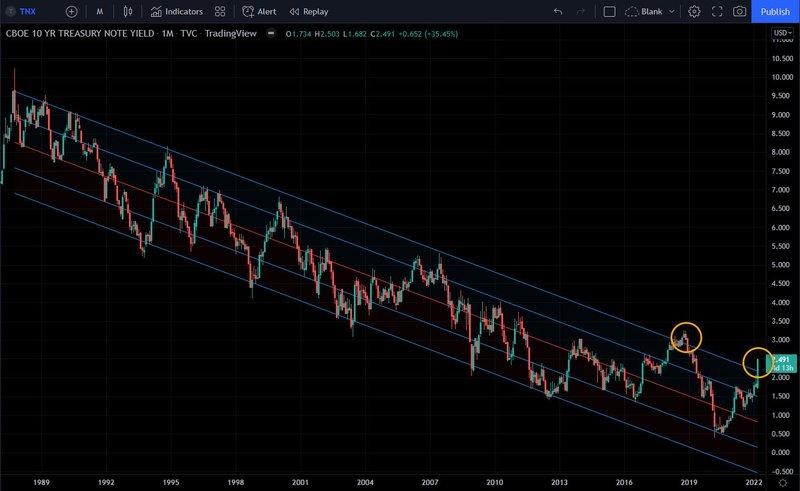

The chart below is of the 10-Year Treasury Note (TNX) yield. The centre (red) line is a regression line and the four blue lines represent one and two standard deviations from the line of best fit. Note that 10-year yields appear to be breaking out and changing trend from down to up. You can see they did have a false breakout in 4Q2018, so a breakout of the long-term downtrend here is not a given. It is, however, a development well worth watching.

I have much more to say on this entire subject, particularly with regard to inflation’s social and household wealth implications. I will share these with you in the coming days, in a separate note.

In closing...

For now, I want to leave you with two possibilities for your consideration:

- Inflation is likely to be (much) higher than the Fed’s target for longer, unless we hit a recession.

- The downtrend we are seeing in bonds (uptrend in bond yields) could be the beginning of a secular trend, unless we hit a recession.

Learn more about Simon Ree at taooftrading.com.