We have successfully navigated a number of damaging bear markets over the past 40 years — the first of which was the 1987 Crash, recalls Jim Stack, money manager, market historian and editor of InvesTech Research.

What is overlooked in today’s bear market and recession debate is how long it often takes for a major bear market to unfold, and the number and size of tempting rallies that occur all the way down.

The sharp rally in July and August has triggered widespread expectations and hopes that the 2022 bear market is already over. We are skeptical — because we know too much about stock market history.

So before jumping on that anticipatory bullish bandwagon, we want to share an insightful lesson about past major bear markets that turned out to be much larger and longer than originally expected.

The historical truth is that protracted bear markets can have numerous rallies, with some seemingly qualifying as a new bull market (+20%) — except for our requirement that a new 12-month high must also be hit.

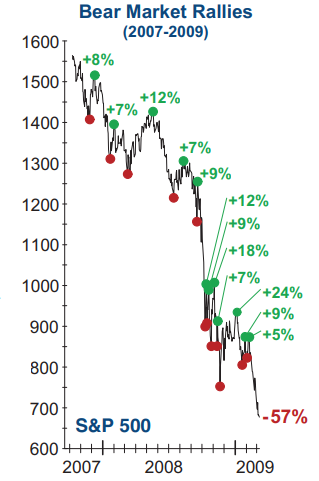

2007-2009

The 2007-09 bear market started out as a widely expected soft landing as overheated housing prices had already cooled, commodity prices peaked, and the Federal Reserve made 5 swift Discount Rate cuts between late January and April 2008.

But the exuberant 12% rally quickly turned into a freefall as the impact of the deflating Housing Bubble quickly spread and the Great Recession took hold. Nonetheless, there were four 10%+ 600 rallies and twice as many 5% bounces on the way down.

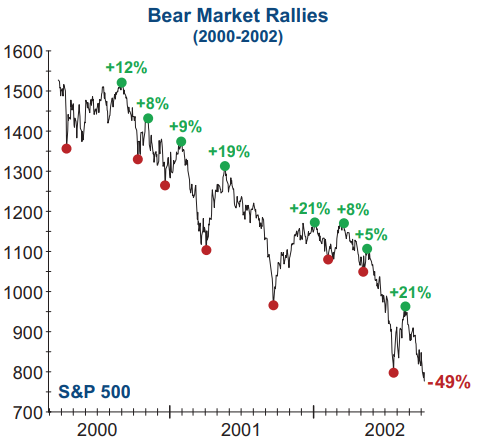

2000-2002

The unwinding of the Tech Bubble in 2000 also started slowly, and the market almost hit a new high in September. With multiple Fed officials still denying a recession was imminent in April 2001, a 19% rally unfolded — yet the worst of the bear market was still to come. Again, there were four alluring 10%+ rallies, and twice as many 5% bounces.

1973-1974

The 1973-74 bear market was driven by persistent inflation and consistent rate increases throughout by the Federal Reserve. Nonetheless, a brief respite of inflation/recession fears triggered a rally in the fall of 1973 that had many convinced the mild bear market was already over. It wasn’t!

1938-1942

Another of the (greater than) 40% bear markets in 1938-42 turned into a 3 1/2-year ordeal, with a number of strong rallies to suck investors back in.

Some analysts like to break this into three separate bear markets because of the 20% rallies, but we’ll stick with our definition: A quick, sharp psychological bounce that doesn’t hit a new 12-month high or sustain long enough to do so, is just a rally.

1937-1938

There were five rallies of 10% or greater in the relatively short, but severe, 1937-38 bear market. Once again, lots of tempting traps for overly anxious premature bulls to jump back in.

1929-1932

The granddaddy of bear markets in 1929-32, of course, had the largest number of 5% and 10% (and five 20% +) rallies. Note that by the spring of 1930, stocks had recovered over one-half of their 1929 Crash losses!

Yet the economic foundation of the speculative 1928-29 excesses was crumbling, and those who didn’t see or heed the warning flags had to endure a long and painful path down to a final bear market loss of 86%.

In Summary

Our objective with these studies is not to convince you that the 2022 bear market is still intact and has a long way to run. It is simply to reveal why we’re not overly concerned about missing the latest stock market rally.

Bear markets are the ultimate test of patience, discipline, and endurance. This bear market is no different, as the S&P 500’s worst 6-month start to a year in over a half century has given way to a rebound since mid-June. While no one likes missing out on gains, exploring past bear markets can help to put the current rally into perspective.

We are certainly not one to complain about the possibility of peak inflation and the welcome respite in price action over the summer. However, we have not been buyers of this rally given our assessment of the sticky nature of inflation, the continued deterioration in leading macroeconomic data, and the lack of bullish confirmation from longer-term technical indicators.

The objective of risk management is not to predict bull market peaks or pinpoint bear market bottoms. Instead, it is to follow a disciplined “weight-of-the-evidence” approach that will lead to increased defenses when market risk is highest... and help to identify the safest buying opportunities once a bear market has run its course. In our view, evidence shows that we are not there yet.