Sponsored Content – Chris Loeffler, CEO & Co-founder of Caliber asks: Have you ever bought canned tomato sauce at the grocery store? Who knew there were so many kinds? How do you choose?

You could pick based on volume, meaning the price per ounce sticker is your best guide. If you’re someone who cares more about the quality of the ingredients, then reviewing the label on the can is the way to go. Or you may believe that one specific brand of tomato sauce gives you the best flavor and results, so shopping is done as soon as you locate it.

There are over 8,000 real estate funds worldwide. According to Preqin, real estate assets under management have grown from $64 billion to over $1 trillion and counting over the last 20 years. Investors choose real estate because they believe it’s a suitable way to make money, whether it’s the primary way they grow assets or to complement an existing portfolio.

Getting to the right “aisle” in the real-estate category means choosing the profile of investment that’s aligned with your goals.

- Do you want more growth or income?

- Do you prefer apartments or office buildings?

- Would you like to renovate something or prefer to see it built from scratch?

- What part of the country would you like to invest in?

These are the types of questions that can help guide you in the type of fund that may be right for you.

Like picking the right tomato sauce, understanding the internal rate of return (IRR), cash-on-cash return, and equity multiple can help you decide between two otherwise similar real-estate deals.

While each metric is a projection, these figures can provide context to the sort of deal the sponsor offers and whether it’s the right investment for you.

Let’s walk through how to use each metric (and its limitations).

Cash-on-Cash Return

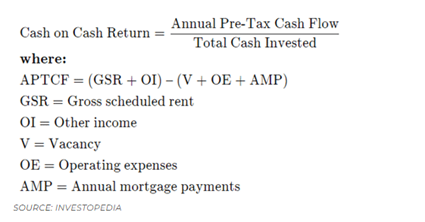

As the name implies, cash-on-cash return[1] calculates the amount of pre-tax cash income an investor could receive from a property based on the amount of cash invested. It’s expressed as a percentage of the property’s cash flows. So, if you see an 8% cash-on-cash return, that means you’d expect to $8,000 in a year on $100,000 invested. Simple, right?

To calculate cash-on-cash return, divide the annual pre-tax cash flow (“APTCF”) from the total cash invested. Annual pre-tax cash flow accounts for the property’s profitability. It includes gross scheduled rent, other income, vacancy, operating expenses, and annual mortgage payments.

[1]Alternatively known as cash yield

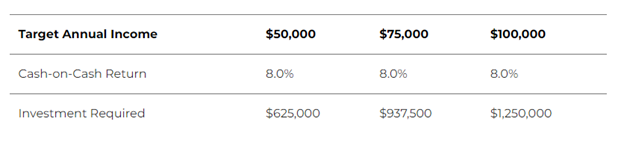

Use cash-on-cash return to approximate how much you’d need to invest to generate a specific annual income. For instance, suppose you were comparing three potential investments that each feature an 8% cash-on-cash return. You could use the cash-on-cash return to gauge how much you’d need to invest to generate a target annual income.

The cash-on-cash return also communicates the project’s expected risk. Higher cash-on-cash returns imply a higher degree of expected risk. Intuitively, that makes sense: the sponsor offers a higher yield for riskier projects to encourage investment. Suppose you targeted an annual income of $100,000 from your next real estate investment. There are three investments under consideration, each with different cash-on-cash returns.

Notably, cash-on-cash return does not account for the time value of money. This means that if the property returned $8,000 after two years instead of one year, the cash-on-cash return would be 8%, but the investment would be inferior to a deal that returned $8,000 in one year.

Cash-on-cash return differs from return on investment (“ROI”) in one key point: it does not account for the commercial property’s debt burden. Most commercial real estate investments involve borrowing money at some point, whether for renovations, to purchase new furniture and fixtures, or something else.

ROI factors in the cost to borrow, whereas cash-on-cash return, does not, leading to a disparity between the two figures. Often, though, sponsors only quote cash-on-cash returns in the offering documents for investors to consider.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

IRR calculates the profitability of an investment over the life of the investment. Most commercial real estate investments take years to go full cycle (acquiring, improving, disposition), and IRR can illustrate the expected return over that period. In other words, IRR can tell you how long the sponsor estimates it will take for you to get your money back.

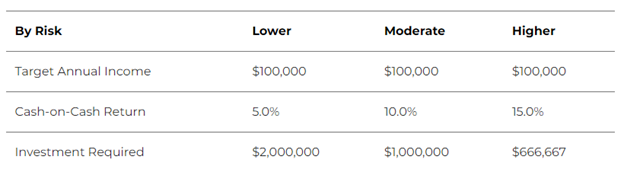

For example, suppose you plan to invest $100,000 in one of two investments. The sponsors for each investment estimate $150,000 of cash flow, to be repaid over seven years. The first investment offers immediate payment of $5,000 per year for the first six years, then a balloon payment of $120,000 in year seven. The second investment offers no payment for the first two years, then $30,000 per year through years three to seven. Which is the better deal?

Despite Investment A offering immediate payment, the higher repayment offered by Investment B produces a better IRR. That’s because you’re receiving more of your money back with Investment B, even though you have to wait two years to see any cash flow.

IRR is expressed as a percentage, so it doesn’t capture the dollar returns that a project could produce. For example, suppose you invested $50,000 in one investment and $200,000 in a second investment. In the first year, the first investment returned $25,000, while the second investment returned $50,000. In this scenario, the first investment has a higher IRR through year one, but you got back more money from the second investment. Depending on the rest of the projected cash flow, the second investment may be the better option.

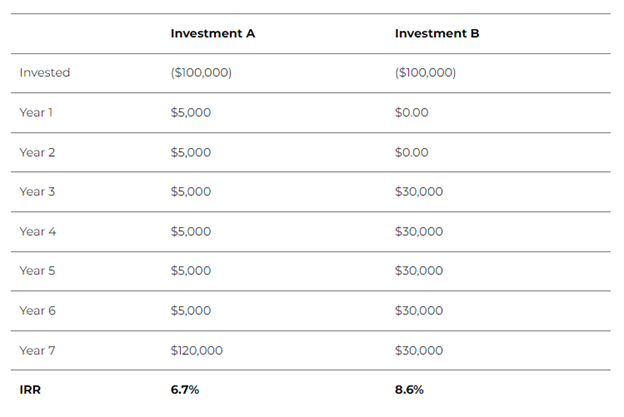

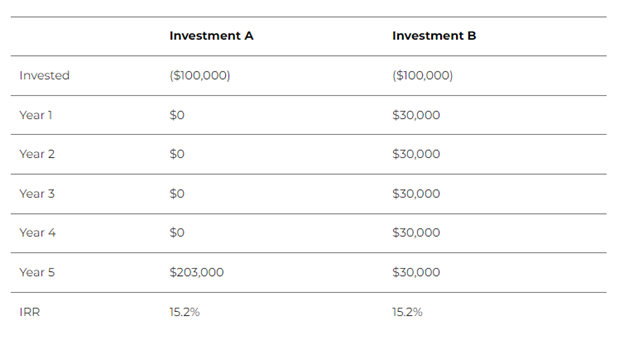

IRR also may not adequately capture when the money is distributed if the sponsor only quotes the total expected IRR for the project. It is possible to have two potential investments with the same IRR where one produces annual income while the other produces income at the end of the investment’s life.

You see more money from Investment A, but a more consistent income from Investment B, and both feature the same IRR.

Equity Multiple

The equity multiple is a simple metric that illustrates how much money the project returned to its shareholders, usually expressed as Nx. A project with an equity multiple of 1x broke even—it did not lose nor generate any profit. So, $100,000 means $100,000 returned. A project with an equity multiple of 2x doubled your investment, and so on.

The formula for equity multiple is (total profit + cash invested)/cash invested.

Like cash-on-cash return, equity multiple does not account for the time value of money like IRR does. For instance, suppose you’re considering two hotel investments. The first investment features an equity multiple of 2.5x, where the second investment features an equity multiple of 1.5x. Based on multiple alone, the first one would seem the better choice.

However, if the first investment takes ten years to return your capital, whereas the second investment takes five years, the second investment may be the better choice, even if the multiple is lower. Situations like these are where IRR and an estimated annual distribution schedule can be very useful to inform your decision.

Limitations aside, equity multiple is arguably the most important metric because it represents the expected total return on your investment.

Putting It Together

The best products at the grocery store combine price, value, and flavor, even if it’s as simple as tomato sauce. Together, IRR, cash-on-cash return, and equity multiple communicate the investment return profile to potential investors. That way, you can find the investment that fits your objectives, whether that’s growth, income, or a balanced approach.

Don’t miss out on your opportunity to tap into Caliber’s real-estate expertise in acquisitions, asset management, and its ability to sell, refinance, and reinvest. Now is the time to build your wealth and transform communities today with caliberco.com.