For the better part of 2022, the about-face and stampede to raise rates by the Federal Reserve have certainly put pressure on US stocks, bonds, and, to some extent, housing, explains Bryan Perry, editor of Cash Machine.

But more importantly, the Fed leaders’ actions are accelerating the chance of something, or some things, breaking in foreign markets. The Fed can be considered the global central bank that pretty much dictates how other central banks will shape monetary policy, leaving financial regulators elsewhere without much choice if they want to support their respective currencies.

It is this main focal point that will likely be the cause of the sound of something “snapping” overseas in the form of a major debt default by a large emerging market, freezing of liquidity within the sovereign bond market, or some nonlinear price action within the foreign exchange (forex) market, where a major currency just decouples under panic selling. Per a recent statement of the World Bank in September, rising global borrowing costs are heightening the risk of financial stress among the many emerging markets and developing economies for the past decade and accumulating debt at the fastest pace in more than half a century.

Even as massive swings in British bonds, amid policy missteps by Prime Minister Liz Truss, forced the Bank of England to intervene and let pension funds unwind risky bets, its actions served as only a temporary shoring up of the pound’s free fall. This past week, the British pound started to roll over, and it may well revisit or even take out the Sept. 28 low.

What’s to stop this from happening with the dollar index, which tracks the dollar against a basket of advanced-economy currencies, from rising beyond its 20% climb over the past year? The move against emerging market currencies has been considerably more dramatic both in terms of exchange rate and inflation. Much of emerging market debt issued has to be paid back in dollars, and all oil transactions around the globe are conducted in dollars, which is considered the world’s reserve currency.

If or when something breaks, it could be linked to a debt servicing crisis. A recent Allianz report concluded that “current debt-to-GDP ratios in France (113%), Italy (151%), and Spain (118%) imply a herculean fiscal consolidation effort to avoid an interest hangover” as debt-servicing costs explode higher. Japan’s government debt accounted for 231% of the country's nominal gross domestic product (GDP) in June 2022, compared with a ratio of 229% in the previous quarter. Last Tuesday, the yen broke a new 24-year low against the dollar, down roughly 27% in 2022 alone.

As troublesome as the weaker currency issues are in the United Kingdom, the European Union, and Japan, it seems the biggest near-term risk of that sound of glass breaking in the distance will be with emerging market debt. A systemic sell-off could be in the making, given the dollar’s rise that intensifies debt levels in emerging markets. Without a policy change by the Fed to all but freeze the $95 billion per month quantitative tightening program, it just might be the force that breaks open the dam.

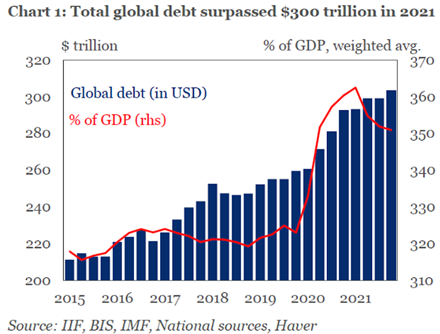

Emerging market borrowing, led by China inflating the global debt mountain to a record $303 trillion in 2021, shows the global debt-to-GDP ratio improved as developed economies rebounded, the Institute of International Finance said. The $10 trillion rise in the global debt pile was down from the $33 trillion increase in 2020 when Covid-19-related expenditures soared. But more than 80% of last year's new debt burden came from emerging markets, where total debt is approaching $100 trillion, the institute reported in its annual global debt monitor report.

The most widely traded emerging market bond exchange-traded fund (ETF) is the iShares JP Morgan USD Emerging Markets Bond ETF (EMB), with about $13.8 billion in assets under management, trading roughly seven million shares per day. It is about as close of a reflection of the health of the non-developed world debt market as can be, in terms of getting a real-time measure for the broad market of this particular asset class.

Because this is a managed fund, it doesn’t represent the gravity of the risk in the broader scope of the emerging market debt market, as China represents just 1.88% of assets. Other highly leveraged countries also have smaller positions.

More importantly, though, this fund has Mexico as its largest holding. As Mexico is the largest trading partner with the United States, the fund is getting crushed, falling 30% year to date (YTD), as both the dollar and interest rates rise to fend off inflation. The chart of EMB is flashing red and should be seen by the Federal Reserve as a market where it’s not a matter of “if” but “when” it breaks because the biggest holders of emerging market debt are the banks of those countries issuing the debt, as well as a large amount held by European banks.